How long does it take for a patent to get accepted in different countries?

How long does a patent to get accepted (‘patent pendency’) in different countries? This appears to be a fairly straightforward question, but can be difficult to answer in practice. However the patent search database Patseer has the ability to report this data, so we have looked at this question from the viewpoint of Australian patent applications.

To answer this question, we ran a search in Patseer for granted patents with Australian priority filings, and published since January 2018. Innovation, utility, design and plant patents were removed from the data, and this left a dataset of around 17,200 patents. Note that this data is PCT patents is based on the official filing date for the patents, which is the filing date for the PCT patent in many cases.

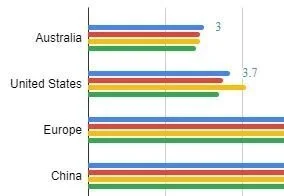

The results are shown below. The countries are ranked according to the number of granted Australian-priority patents. I have also determined the same data for patents within three specified and popular ‘Industries’, with the inclusion of patents within these industries predicted by Patseer. Unfortunately, similar data was not published by Patseer for New Zealand and Indian patents.

So what are the key takeaways?

Average time to acceptance varies widely, from just 2 years in Singapore to 10.2 years in Brazil.

Australia had the second shortest average grant times in this list, followed by the United States and Russia.

There were also variations for each country in the Industry category, but this variation was much less than between countries (mouse over each bar to see the value).

There were no consistent trends across the different Industries for the different countries.

Why are there such variations?

This is a great question. I have had extensive discussions with a long-established specialist in this area, and I suspect that it comes down to the following factors:

Different examination practices between countries. For example, Australia generally sends out a Direction to request for examination some times after the filing date, and now allows a maximum time to gain acceptance of 12 months. This period of pendency has decreased since the Raising the Bar Act.

Other countries, such as Canada, China, Japan, and the European Patent Office, have ‘exam request’ systems. These are similar to Australia, except that the offices do not have the power to compel applicants to request examination. Many applicants therefore choose to request exam close to the relevant deadline. Those deadlines (measured from the original filing date, i.e. international filing date for PCT applications) are three years for China and Japan, and six months after advertisement of the European Search Report at the EPO. The deadline is currently four years for Canada, but up until 30 October 2019 it was five years – and that is what we are seeing reflected in the pendency for patents granted recently. None of these jurisdictions has a fixed examination period like Australia, but they do have varying deadlines for responding to each individual examination report. On the other hand, most will not allow the applicant to persist with examination indefinitely, as in the US.

In contrast, the likes of the US start examination when the patent arises in the queue - and they may be different queues for different technologies.

This data may be affected by divisional applications, which can be examined in less time than original applications. The rules for divisional applications can range from country to country.

And lastly, it may be that some patent offices are simply faster or slower to examine patents, due to resourcing levesl, internal policies, or other reasons.

I will leave determining the exact reasons for the above country-by-country variations to others, but equally, it is worth asking ‘does average time-to-grant matter?’

Does the time-to-acceptance matter?

A patent is intended to provide a monopoly for a finite time for deserving inventions, in order to encourage both the commercialization and publication of new ideas.

As such, a patent application and its legal status affects a range of people.

From an applicant's perspective, some prefer a patent to be granted because of its perceived status, greater legal certainty, and the right to sue alleged infringers. Others are happy to drag out the grant process to both defer the costs of examination, and also to provide maximum flexibility against infringers. Some applicants for some patents even immediately filed a divisional or continuation-in-part application as soon as a patent is accepted, in order to maximise their flexibility going forward.

We should also consider the perspective of competitors to the applicants and other people who might want to use the same technology. An active patent application comes with a degree of uncertainty about which claims will eventually be accepted, particularly as the claims of most patent applications are deliberately broad as possible in an ambit claim. The competitors, if they do come across the patent application in the likes of a Freedom-to-Operate review, then have to engage in an exercise to try to predict the likely scope of the granted claims. This prediction can be costly and uncertain.

Practically, this means that the applicant for a pending patent gains two benefits, namely that provided by their patentable invention - which is fair and deserved - and an additional benefit due to the uncertainty of the scope and status of the active patent application. I am not sure that this additional benefit is fair and deserved, and for this reason, I would suggest that we are better off with shorter rather than longer patent pendency to acceptance times.